Condemning the West is as morally dangerous as it is intellectually bankrupt.

For centuries, science fiction has captured the Western imagination, fueling our sense of the future with tales of wonder as well as words of warning. But in modern times, the genre has all too often fallen captive to writers who have gone sour on humanity itself. In a recent episode of the new Star Trek series Picard, the crew crashes in Los Angeles in the year 2024. There, amid a throng of vagrants and ICE agents, an alien resident on Earth since the eighteenth century condemns the backwardness of the human species.

The scene is hardly an isolated incident. The hopelessness and stupidity of humanity is one of the show’s central themes. How willfully ignorant does a TV writer have to be to believe that someone—even an alien—who witnessed hundreds of years of human history, watching things improve rapidly, would somehow end up with a hostile view of the early twenty-first century? We have serious problems to fix, but an eighteenth century human would laugh about what we include as problems in the twenty-first century. One of the problems the characters complain about as a prime example of humanity’s failure is “online disinformation”—as though this issue legitimately ranks among war, pestilence, and famine as a problem of historical significance. Somehow, the more petty our foibles, the more harshly they condemn us.

What’s behind the largely negative mood of the current historical discourse? The doomsaying comes in disproportionate measure from people tweeting about the mistakes of the past in high-rise apartments in clean and functional neighborhoods in the richest country in the history of the world. Safe and comfortable in their pods, they vehemently scorn those of us who are proud of our civilization and what it has uniquely accomplished for humanity.

It’s not totally clear why so many hold our past (and even the present) in such extreme contempt, but there is probably a combination of factors:

- The West “won,” and some feel guilty about that;

- There are far more written records of the West’s mistakes and crimes than those of other civilizations;

- In its decadence, the West has become bored and enjoys self-criticism;

- Attacking the past is a good pretext to seize political power today.

If it were just these adults sitting around alone being cynical, maybe we could put up with it. But the negativity has been percolating for some time, infecting education, politics, and other institutions with a constant demand for historical shame, abject apology, and, somehow, a new civilization purified of all that came before. This misanthropic revolution threatens our future as well as our past. It’s time we deal with it.

To start, we can identify key elements that constitute “the West” as a value system that has grown and developed for millennia, drawing from classical wisdom, Judeo-Christian faith, and Enlightenment politics.

No one of these on its own is enough to make a just society. The classical world was brutal. The deeply fractured world of pre-Enlightenment Europe suffered from slow and volatile growth. The extremes of the Enlightenment, striving to cleanse life of all that was “irrational” in tradition, led to the Terror of the French Revolution and other destructive obsessions aimed at imposing social uniformity. But America’s history has shown that classical wisdom, modern knowledge, and ancestral faith can combine to foster achievements unique in history, an unparalleled track record of self-improvement. Under our leadership, the West hasn’t just triumphed over others; we’ve triumphed against ourselves.

In the thirteenth century, with Magna Carta, America’s mother country England placed the King firmly under the rule of law; centuries later, amid the Glorious Revolution, England rejected the arbitrary power of the monarch and the star chamber and introduced a Bill of Rights; and in 1776 and 1789 some former English colonies rejected monarchy outright and forged, on classical, modern, and biblical foundations, a truly novel government.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” That one sentence marks the origin point for a 250-year arc of radical global progress, and not just in the new nation that produced it. America wasn’t perfect, but it had exactly the right framework in place to realize the goals of the Declaration and to pursue over time the expression of extraordinary ideals.

In this country, we have cultivated a unique respect for the rights of the individual. Our Constitution has served as a positive governance model to countries all over the world, including those with cultural milieus quite distinct from our own. Our cultural and governance frameworks allow different people to live and prosper together more than any other society in history. And when problems need to be addressed, our value system provides the corrective mechanisms. Fully conscious of this advantage, Martin Luther King, Jr. directly invoked the Founding in his “I Have a Dream” speech: “When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir.”

That note was first redeemed when in 1865 the U.S. rectified the crime of slavery. Slavery was, of course, not at all unique in history; what is unique in history is the vision of our national founders, who have served as a font of moral authority for successive generations, even across a considerable difference of time and relative values.

It’s unacceptable to brainwash young people deprived of a historical background to believe that America or the West is evil and that we should be ashamed of ourselves. History is full of sins and contradictions, no doubt. But on the big questions—is America a terrible place? Are Europeans in the last 500 years uniquely bad in history? Are we so immoral as to warrant the systematic destruction of our nation and Western civilization?—there is really just one answer: No.

To show why, let’s recall a few points of history.

The Americas

My alma mater, Stanford, has recently erased the name of the Catholic missionary Saint Junipero Serra from its campus. Serra, in many ways the founder of modern California, has a mixed record by today’s standards (like a lot of people from the sixteenth century). He was canonized by Pope Francis in 2015. Just a few years later the university, under pressure from activists, denounced Serra and purged his name. At around the same time, they introduced an official university “land acknowledgment” for the Muwekma Ohlone, one of the indigenous groups that lived in the area where Stanford is today. The trustees of Stanford aren’t going to give the land back—obviously—but this kind of empty virtue signaling is now all but mandatory at many universities.

Given that Stanford seems to have a lot of thoughts about Europeans in the colonial period, one wonders whether they have any opinion about the relative moral virtue of the Muwekma Ohlone tribe and its history. But moral judgements at Stanford and other universities apply only to one side: the colonizers, the Europeans, the Christians, the Americans—in sum, the West. We don’t ask any questions about whether non-Western groups in history may have also done bad things—perhaps because of how uncomfortable it would be for a left-wing university to take a look at the history of the Americas before the supposedly evil Europeans arrived.

The Americas were an incredibly cruel place. In the Aztec Empire, one of the best-developed American civilizations, human sacrifice was a centrally important state practice. Conservative estimates put the scale of the sacrifice in the range of tens of thousands per year, for centuries. Living people had their chests slashed open by priests, their hearts torn out, and their mutilated bodies thrown down the temple steps.

The Australian historian Inga Clendinnen details the Aztec ritual of child sacrifice:

The children were kept by the priests for some weeks before their deaths (those kindergartens of doomed infants are difficult to contemplate). Then, as the appropriate festivals arrived, they were magnificently dressed, paraded in litters, and, as they wept, their throats were slit: gifted to Tlaloc the Rain God as “bloodied flowers of maize.” (They were thought then to enter the gentle paradise of Tlaloc, which may have assuaged the parents’ grief.) The pathos of their fate as they were paraded moved the watchers to tears, while their own tears were thought to augur rain.

It should not be controversial to say that the sixteenth-century Catholic or Spanish visions of the world aren’t remotely comparable to the cult of Tlaloc. The Inquisition was one of the worst periods in pre-modern Europe, especially for Jews. But there are single weeks in Aztec history during which more were sacrificed than were killed in centuries of the Spanish Inquisition (estimated in the thousands).

It’s a good thing for humanity that the Aztec moral vision of the world—that slitting babies’ throats makes crops grow—is no longer current. And while nobody is taking a victory lap about the deaths of Mexica (the main Aztec group) or any other indigenous groups, the Christian transformation of Mexico was for the better. And we should also recognize that it wasn’t the Spanish alone that put an end to the Aztecs. The conquest would have never succeeded if not for other Mesoamericans, former victims of Aztec cruelty, who joined with the Spanish.

As is clear to anyone, Christianization and colonization didn’t make Mexico a perfect society, but I, like so many others, have no regrets that Aztec sacrifices are in history textbooks, and not the evening news.

The Aztec state, by modern estimates, was probably the most lethal state in history on a percentage basis, with greater figures dying in war than in any other. And yet, the Aztec state looks almost serene compared to the rates of war death in non-state societies, many of them in the Americas. The Kato people in Northern California had—by a considerable margin—the most violent society in human history.

From The Better Angels of Our Nature by Steven Pinker (Viking, 2011)

I wish I didn’t have to go back in history and point out these terrible things: I want to look to the future. But given the myopic focus on the negative aspects of our own history, the context is more than warranted.

Even more recently, Americans have had a grim history hidden from them. Take, for example, an Army sergeant’s recollection of what a band of Kiowas did to a wagon train in Texas in 1871:

Stripped stark naked and fastened by a chain in the fire was the body of the wagon master of the train. One side was burned to a crisp and the limbs were twisted out of all shape by the action of the flames. He had been scalped alive and hot ashes poured upon his bleeding skull, and, notwithstanding all this, life was not yet extinct, as was evidenced by his wildly rolling eyeballs.

Unfortunately, stories such as the Warren Wagon Train were common over the American frontier. And unless you’re able to realize just how harsh a lot of history is, you won’t realize just how good we have it. Values matter; individual rights matter.

The Twentieth Century

The twentieth century was a bloody mess, and arguably it poses the most direct challenge to the idea of the West, given that much of the bloodshed happened in Europe, in the shadow of Enlightenment and Judeo-Christianity.

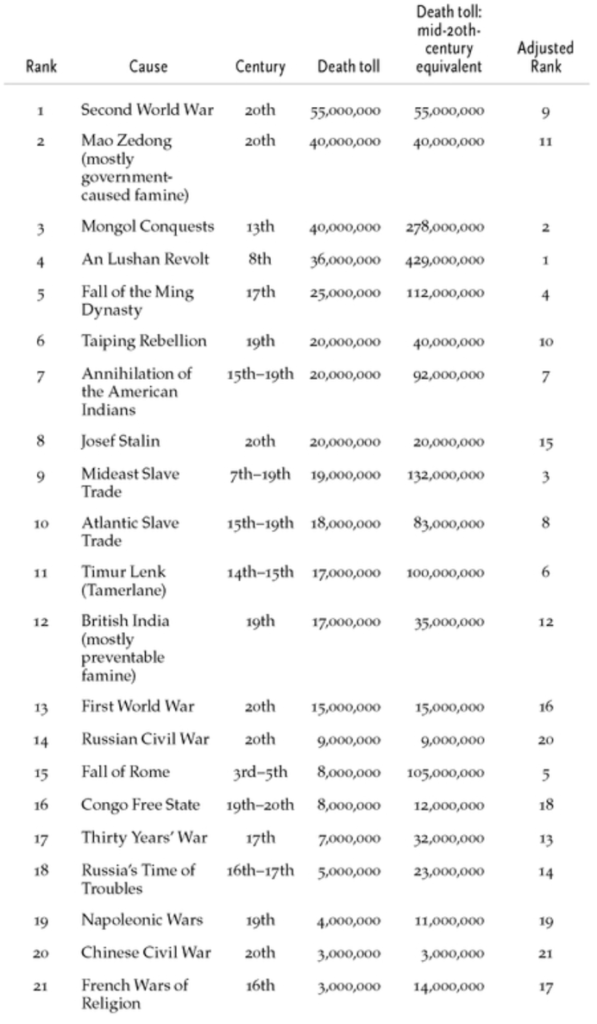

But it’s worthwhile to take a quick look at the death toll in context. First: the vast majority of deaths in the Second World War were inflicted by the Empire of Japan against Chinese civilians and by Hitler’s military against Soviet and East European soldiers and civilians. And second: on a population-adjusted basis, there were periods of warfare and revolt in pre-modern Asia that killed more than the entire twentieth century combined.

From The Better Angels of Our Nature by Steven Pinker (Viking, 2011)

From The Better Angels of Our Nature by Steven Pinker (Viking, 2011)

After the Second World War, the West led the world toward major course corrections: over the long competition with Communism, peoples increasingly embraced the restoration and adoption of Western values with a good conscience. The extreme divergence since then between societies that embraced Western values and those that didn’t is a compelling case for the utility and virtue of those values. And the horrific fate of Western nations that sought to transform themselves by force into a spiritually pure successor civilization is a potent lesson for today’s revolutionaries. The villains of the twenthieth century expressed a self-loathing strain in the West that sought to annihilate its core values of individual rights, human equality, and reason supported by revelation. Instead, they only succeeded in annihilating innocent life—and, finally, themselves.

The Westerners who picked up the pieces, by contrast, did remarkably well, both for themselves and others. The 1946 Japanese constitution, written largely by American lawyers under the supervision of Douglas MacArthur, with the review of Japanese scholars, produced one of the most prosperous countries in history. It’s almost unbelievable that Japan, which was destroyed in 1945 materially and spiritually, became the second-largest economy on earth by the end of the century. (West Germany, in shining contrast to East, experienced a similar renaissance.) While the Japanese GDP was exploding upward in the 1960s and while Singapore was developing into an impressive city state, just across the water the Chinese Communist government under Mao Zedong caused the largest famine in history, killing roughly the same number as the Second World War.

Where do the victims of Communism go to get their reparations? Where do they get their apologies? They don’t. The recourse for people in those societies is most often to exit, which they have done en masse. Perhaps it should serve as an indicator to us that something is going badly wrong in this country when those survivors warn us that their history is beginning to repeat itself here at home. And perhaps it’s an indicator of all we do right that the survivors of the worst regimes in recent memory are so desperate to get here. It’s not just economics influencing that decision. They understand the foundational importance of this country’s values, even though they weren’t taught them.

The story of human history is largely one of different groups oppressing other groups: wiping them out, enslaving them, abusing them, etc. It’s not a rosy picture. Humans are naturally tribal and envious. Fueled by vengeance and rivalry, we’ve treated one another horribly on this planet. But our humanity is not a problem to be solved or a sin to be expunged. It’s a destiny we can and should live up to.

I come from two groups that haven’t exactly received stellar treatment over the years—the Jews and the Irish. And contrary to accusations from some on the Internet against me: no, I don’t think that the crimes committed against Jews or anyone else were somehow “worth it” or that the present prosperity legitimizes the bad treatment. Of course not. But it’s simply not true that the historical negativities were inherent in the nature of the West. In most cases, it’s plain to see they were aberrations. If you can’t separate out the bad parts from the bigger story and recognize that today we have largely made up for our civilizational mistakes, then you shouldn’t be in the business of talking about history. No matter how ostensibly “ethical,” the lack of context is as ridiculous as it is dangerous.

To me, the Judeo-Christian worldview’s special emphasis on the equality of humans before God, and the dignity of each person as an individual, is essential. Judaism’s most important single teaching is our creation in the image of God—the bedrock of our equal and individual intrinsic value. From here sprung the idea that all human beings are family, all children of the same eternal parent, and that each of us has a soul bearing the stamp of the divine. This isn’t a trivial view, as we saw in the Americas.

But at its best, the West is confident enough to recognize that we do not have a monopoly on moral wisdom and values. There are great things to be studied in cultures the world over. Consider the East. Sacred texts like the Bhagavad Gita express deep truths about personal ethics, motivation, and duty; canonical teachings from Laozi, Confucius, and the Buddha impart enduring lessons about authority, responsibility, and rectitude.

Yet even in non-Western societies like India and China, it’s plain to see the utility of fusing tradition with the Western ideas about markets and freedom that have lifted up billions into an age of unprecedented global prosperity. In our own country, even as we benefit from lots of cultural traditions—maybe more than any other country in the world—we still need one set of values to ground ourselves, on which we wager our future. The only values that can ground us in this way are the same ones that have made our national culture genuinely unique from the beginning.

It’s absolutely fine to teach and learn about the beauty and wisdom that comes from other cultures. What isn’t fine is to teach that our own is evil and immoral. Our children will be bereft of the foundation they need to understand why our country works; why it is that people from all over the world want to be here; and how we can apply these values to make our future even better.

We should be biased toward pride in our civilization, and we should harness that pride in order to build new things. If we teach children that our past is evil and irredeemable, then they’re going to think our future is, too.

Solving problems is hard, and retrospective moral judgment is very, very easy. But we should have high expectations for ourselves, because we can be great. We should do the hard thing.

The word “nihilism” comes from the Latin nihil—nothing. If we continue to indulge the historical nihilism that ignores the unique and positive qualities of the West and of our country, that’s exactly what the future holds: nothing.

For my part, I’m doubling down on the values of our civilization. Let’s build great things, tell stories of human achievement, improve governance, inspire young people, and have appropriate reverence for the past—not out of pure nostalgia for yesterday, but as a reminder that it’s in our power to use the right values to build an even better tomorrow.

Apareció primero en Leer en American Mind

Be the first to comment